QPU

Template:Infobox computing device

A Quantum Processing Unit (QPU), also known as a quantum processor, is the core hardware component of a quantum computer that manipulates qubits using the principles of quantum mechanics to perform computations that are intractable for classical processors.[1][2] Unlike classical CPUs that process bits in binary states (0 or 1), QPUs leverage quantum phenomena such as superposition and entanglement to process qubits that can exist in multiple states simultaneously, enabling exponential scaling of computational power for specific problems.[3]

QPUs are designed to solve complex problems in cryptography, molecular simulation, optimization, and machine learning that would require impractical amounts of time on even the most powerful supercomputers.[4][5] As of 2025, the field has achieved critical breakthroughs including Google's demonstration of below-threshold quantum error correction with their Willow processor and IBM's roadmap to 200 error-corrected logical qubits by 2029.[6][7]

Overview

The QPU represents the quantum analog to the classical CPU, serving as the computational heart of quantum computers. However, this analogy can be misleading—QPUs are more accurately described as specialized co-processors similar to GPUs or TPUs, designed to accelerate specific computational tasks rather than serve as general-purpose processors.[8]

A QPU operates by manipulating qubits through quantum logic gates and interactions, forming quantum circuits analogous to classical logic circuits. While classical processors execute operations sequentially or in limited parallelism, QPUs can explore an exponentially large computational space simultaneously—N qubits can represent 2^N states at once, compared to N bits representing only one of 2^N possible states.[9]

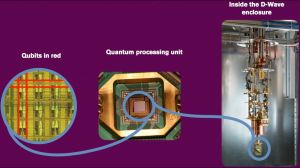

Modern quantum computers integrate the QPU within complex systems including:

- Quantum chip: Physical substrate containing qubits and control elements

- Control electronics: Generates precisely timed microwave or laser pulses

- Cryogenic systems: Dilution refrigerators maintaining temperatures near absolute zero (10-15 millikelvin) for superconducting QPUs

- Classical processors: Handle compilation, error correction, and result processing

- Shielding: Electromagnetic and vibrational isolation protecting fragile quantum states[2][10]

History

Theoretical Foundations (1980-1985)

The theoretical foundations of quantum computing emerged in the early 1980s. Paul Benioff proposed quantum mechanical models of computation in 1980, describing a quantum mechanical Turing machine.[11] Richard Feynman formalized the concept in his 1981 MIT keynote "Simulating Physics with Computers," arguing that quantum computers would be necessary to efficiently simulate quantum systems, and published these ideas in 1982.[12] David Deutsch provided the theoretical framework for universal quantum computers in 1985, establishing that quantum systems could efficiently simulate any physical process.[13]

Early Implementations (1990s)

The 1990s transformed quantum computing from theoretical concept to experimental reality:

- 1994: Peter Shor developed Shor's algorithm for integer factorization, demonstrating exponential quantum speedup for breaking RSA encryption[14]

- 1995: Dave Wineland and Christopher Monroe demonstrated the first two-qubit quantum circuit at NIST[15]

- 1996: Lov Grover developed Grover's algorithm providing quadratic speedup for unstructured search[16]

- 1998: IBM researchers executed Grover's algorithm on a 2-qubit NMR quantum computer[17]

- 1999: NEC demonstrated superconducting qubits using Josephson junctions, establishing the foundation for modern superconducting QPUs[18]

Commercial Development (2000s-2010s)

| Year | Company/Institution | Achievement | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | D-Wave Systems | 28-qubit quantum annealer demonstration | First commercial quantum computing company |

| 2011 | D-Wave Systems | D-Wave One (128 qubits) | First commercial QPU sold to Lockheed Martin for ~$10 million[19] |

| 2013 | Google/NASA | D-Wave Two (512 qubits) | Established Quantum AI Lab |

| 2016 | IBM | 5-qubit cloud access | First public cloud quantum computing service |

| 2017 | IBM/Intel | ~50-qubit processors | Approaching quantum supremacy threshold |

| 2019 | Sycamore (53 qubits) | Claimed quantum supremacy - 200 seconds vs 10,000 years classical[4] |

Modern Era (2020s)

The 2020s have witnessed rapid acceleration in QPU development:

- 2021: IBM's Eagle processor achieved 127 qubits, surpassing 100-qubit barrier[20]

- 2022: IBM Osprey reached 433 qubits; Xanadu demonstrated photonic quantum advantage with Borealis[21]

- 2023: IBM Condor achieved 1,121 qubits; Atom Computing demonstrated 1,180 neutral atom qubits[22][23]

- 2024: Google's Willow achieved below-threshold error correction; Quantinuum reached 99.914% two-qubit fidelity[6][24]

- 2025: Microsoft unveiled Majorana 1 topological qubit prototype (8 qubits); Google reported Quantum Echoes, a verification technique that enabled a ~13,000× speed-up for a molecular-structure task[25][26]

Fundamental Principles

QPUs derive their computational power from three core quantum mechanical phenomena that have no classical analog:

Superposition

Quantum superposition allows qubits to exist in a probabilistic combination of both |0⟩ and |1⟩ states simultaneously, described mathematically as:

where α and β are complex probability amplitudes satisfying |α|² + |β|² = 1.[9]

This enables N qubits to represent all 2^N possible states simultaneously, providing exponential scaling unachievable classically. For perspective, 300 qubits can theoretically process more states than there are atoms in the observable universe.[1]

Entanglement

Quantum entanglement creates correlations between qubits where the quantum state of one qubit cannot be described independently of others. A classic example is the Bell state:

Entangled qubits exhibit perfect correlations regardless of physical separation—measuring one instantly determines the state of others, enabling quantum algorithms to process information in ways impossible classically.[9][27]

Interference

Quantum interference manipulates probability amplitudes to constructively amplify correct answers while destructively canceling incorrect ones. Quantum algorithms carefully orchestrate interference patterns so that paths leading to wrong answers cancel out while correct solutions reinforce, dramatically increasing the probability of measuring the desired result.[27]

Physical Implementations

Multiple competing technologies exist for implementing QPUs, each with distinct advantages and challenges:

Comparison of Leading Qubit Technologies

| Feature | Superconducting | Trapped-Ion | Photonic | Neutral-Atom | Topological |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Qubit | Josephson junction circuit | Trapped ion (e.g., Yb+) | Photon properties | Neutral atom in optical trap | Majorana zero modes |

| Operating Temp | ~15 mK | Room temp (trap) | Room temperature | Room temp (trap) | ~10 mK |

| Coherence Time | 30-300 μs | Seconds to minutes | Limited by loss | ~1 second | Theoretical projection |

| Gate Speed | 10-100 ns | 10-100 μs | <1 ns | 0.1-1 μs | Unknown |

| Two-Qubit Fidelity | ~99.6-99.7% (best systems) | >99.9% | High (probabilistic) | ~99.5% | Theoretical projection |

| Connectivity | Nearest-neighbor | All-to-all | Reconfigurable | Flexible via Rydberg | Unknown |

| Scalability | High (chip fab) | Moderate (modular) | Very high (photonics) | High (optical arrays) | Potentially highest |

| Key Advantages | Fast, manufacturable | High fidelity, long coherence | Room temp, networkable | Scalable, reconfigurable | Theoretical error protection |

| Main Challenges | Short coherence, cooling | Slow gates, scaling | Probabilistic gates | Atom loss | Unproven at scale |

| Leading Companies | IBM, Google, Rigetti | IonQ, Quantinuum | PsiQuantum, Xanadu | QuEra, Pasqal, Atom Computing | Microsoft |

Superconducting QPUs

Superconducting QPUs dominate current commercial systems, using microscopic circuits with Josephson junctions cooled to near absolute zero where they exhibit quantum behavior.[28]

- Advantages: Fast gate operations (10-100 ns), leverages semiconductor fabrication, demonstrated scaling to >1,000 qubits

- Challenges: Short coherence times (30-300 μs), requires extreme cooling, crosstalk between qubits

- Notable Systems: IBM Condor (1,121 qubits), Google Willow (105 qubits with 99.67% two-qubit fidelity), Rigetti Ankaa-3 (84 qubits)[6][29]

Trapped-Ion QPUs

Trapped-ion systems suspend individual charged atoms in electromagnetic fields, manipulating them with precision lasers.[30]

- Advantages: Exceptional coherence (seconds to minutes), highest gate fidelities (>99.9%), all-to-all connectivity

- Challenges: Slower gates (10-100 μs), complex scaling beyond 50-100 ions

- Notable Systems: IonQ Forte (36 qubits, #AQ 35), Quantinuum H2 (56 qubits with quantum volume of 8,388,608)[31][32]

Photonic QPUs

Photonic processors encode quantum information in properties of light particles (photons).[33]

- Advantages: Room temperature operation, minimal decoherence, compatible with fiber networks

- Challenges: Difficult two-qubit gates, photon loss, probabilistic operations

- Notable Systems: Xanadu Borealis (216 modes), PsiQuantum Omega (in development)

Neutral-Atom QPUs

This approach uses arrays of neutral atoms trapped by focused laser beams ("optical tweezers").[34]

- Advantages: High scalability (>1,000 qubits demonstrated), flexible connectivity, long coherence

- Challenges: Atom loss during computation, moderate gate speeds

- Notable Systems: Atom Computing (1,180 qubits), QuEra Aquila (256 qubits)[35]

Topological QPUs

Microsoft's approach uses exotic quasiparticles called Majorana zero modes in specially engineered materials.[25]

- Advantages: Theoretical intrinsic error protection, potential for million-qubit chips

- Challenges: Unproven at scale, limited experimental validation

- Notable Systems: Microsoft Majorana 1 (8-qubit prototype, early stage)

Architecture and Operation

System Components

Modern QPUs integrate multiple subsystems working in concert:

| Component | Function | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chip | Houses physical qubits and coupling elements | Isolation from noise, precise fabrication |

| Control Electronics | Generates/delivers gate pulses | Sub-nanosecond timing, low noise |

| Readout System | Measures qubit states | >99% fidelity, quantum non-demolition |

| Cryogenic Infrastructure | Maintains operating temperature | 10-15 mK for superconducting |

| Classical Processing | Compilation, error correction, control | Real-time processing, low latency |

| Shielding | Protects from environmental noise | Electromagnetic, vibrational, thermal |

Operational Workflow

The execution of a quantum algorithm follows these steps:

- Compilation: Classical compiler translates high-level algorithm into hardware-specific quantum circuits

- Initialization: All qubits prepared in known state (typically |0⟩)

- Gate Sequence: Control pulses apply quantum gates according to compiled circuit

- Measurement: Qubit states collapsed and read out as classical bits

- Repetition: Process repeated thousands of times to build probability distribution

- Post-processing: Classical analysis extracts final answer from measurement statistics[1]

Quantum Gates

Quantum logic gates manipulate qubit states through controlled interactions:

- Single-qubit gates: Rotations around Bloch sphere axes (X, Y, Z rotations, Hadamard)

- Two-qubit gates: Create entanglement (CNOT, CZ, iSWAP)

- Gate implementation: Microwave pulses (superconducting), laser pulses (trapped ion/neutral atom)

- Fidelity requirements: >99.9% for practical error correction[36]

Performance Metrics

Quantum Volume

Quantum volume combines multiple performance aspects into a single metric:[37]

- Accounts for qubit count, connectivity, gate fidelity, and measurement accuracy

- Higher values indicate better overall system performance

- Record: Quantinuum H2 achieved quantum volume of 8,388,608 (2^23) in 2023[32]

Key Performance Indicators

| Metric | Description | Current State-of-Art (2025) | Target for Fault Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | Number of physical qubits | 1,000-5,000 | 1-10 million |

| Coherence Time (T1, T2) | Qubit lifetime | 30-300 μs (superconducting) Seconds (trapped ion) |

Application dependent |

| Single-Qubit Fidelity | Single gate accuracy | 99.95-99.998% | >99.99% |

| Two-Qubit Fidelity | Entangling gate accuracy | 99.5-99.914% | >99.9% |

| Readout Fidelity | Measurement accuracy | 99-99.5% | >99.9% |

| CLOPS | Circuit Layer Operations/Second | 150,000 (IBM) | >1 million |

| Logical Qubit Error Rate | After error correction | 10^-3 to 10^-6 | <10^-10 |

Applications

QPUs excel at problems with inherent quantum structure or exponential classical complexity:

Quantum Simulation

- Drug Discovery: Simulating molecular interactions, protein folding, drug-target binding[38]

- Materials Science: Designing catalysts, batteries, superconductors

- Example: In 2025, Google reported Quantum Echoes, a verification technique that enabled a ~13,000× speed-up for a molecular-structure task, with a method for certifying the result's correctness[26]

Optimization

- Finance: Portfolio optimization, risk analysis, derivative pricing

- Logistics: Route optimization, supply chain, scheduling

- Manufacturing: Process optimization, quality control

- Example: JPMorgan researchers demonstrated certified quantum randomness on Quantinuum hardware; certified randomness is useful for Monte Carlo methods in finance[39]

Cryptography

- Code Breaking: Shor's algorithm threatens current RSA/ECC encryption

- Quantum Security: Quantum key distribution for unbreakable communication

- Resource Requirements: Breaking RSA-2048 with Shor's algorithm would require thousands of logical qubits; one influential analysis suggests ~20 million noisy physical qubits (under specific assumptions) would be needed to factor RSA-2048 in ~8 hours, underscoring that calendar timelines remain speculative[40]

Machine Learning

- Quantum Machine Learning: Enhanced feature spaces, quantum neural networks

- Speedups: HHL algorithm for linear systems, quantum kernel methods

- Applications: Pattern recognition, optimization, data analysis[41]

Challenges and Limitations

Decoherence and Error Rates

- Decoherence: Quantum states decay in microseconds to seconds depending on technology

- Error accumulation: Current error rates of 0.1-1% per gate limit circuit depth

- Environmental sensitivity: Vibrations, electromagnetic fields, cosmic rays cause errors

- Mitigation strategies: Error correction codes, improved materials, better isolation[42]

Quantum Error Correction

Quantum error correction enables fault-tolerant computation but requires massive overhead:

- Physical-to-logical ratio: 1,000-10,000 physical qubits per logical qubit with current error rates

- Surface code: Leading approach arranges qubits in 2D grid for error detection/correction

- Breakthrough: Google's Willow achieved below-threshold correction—errors decrease as more qubits added[6]

- Alternative codes: Quantum LDPC codes promise 10× efficiency improvement

Scalability Challenges

- Wiring complexity: Each qubit needs control/readout lines

- Cooling limits: Dilution refrigerators struggle beyond 10,000 qubits

- Control electronics: Classical processing requirements scale with qubit count

- Solutions: Modular architectures, cryogenic electronics, photonic interconnects

Current State and Future Outlook

NISQ Era (2025-2029)

The current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era features:

- 50-1,000 noisy physical qubits

- Limited to ~1,000 gate operations before decoherence

- Specialized quantum advantages on narrow problems

- Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms (VQE, QAOA) showing practical value

Path to Fault Tolerance (2029-2035)

Industry roadmaps converge on achieving practical fault-tolerant systems:

| Company | 2025 Status | 2029 Target | 2035 Vision |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM | 156-qubit Heron R2 | 200 logical qubits (Starling) | 2,000+ logical qubits |

| 105-qubit Willow | "Useful error-corrected QC" | Million physical qubits | |

| IonQ | 36 qubits (#AQ 35) | #AQ 64+ systems | Scalable trapped-ion architectures |

| Microsoft | 8-qubit Majorana 1 (prototype) | Scalable topological qubits | Million qubits/chip (theoretical) |

| Quantinuum | 56 qubits (QV 8,388,608) | Advancing toward fault tolerance | Commercial quantum advantage |

Market Projections

- Current market: ~$1 billion annually (2025)

- 2030 projection: $5-15 billion (conservative) to $45-72 billion (optimistic)

- Key drivers: Drug discovery, materials science, financial modeling, logistics optimization[43]

See Also

- Quantum computing

- Qubit

- Quantum algorithm

- Quantum error correction

- Quantum supremacy

- Quantum machine learning

- Dilution refrigerator

- Post-quantum cryptography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "What is a QPU (Quantum Processing Unit)?". IBM. Retrieved November 3, 2025. URL: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/qpu

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Merritt, Rick (July 29, 2022). "What Is a QPU?". NVIDIA Blogs. Retrieved November 3, 2025. URL: https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/what-is-a-qpu/

- ↑ "What is a Quantum Processing Unit?". QuEra. Retrieved November 3, 2025. URL: https://www.quera.com/glossary/processing-unit

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Arute, F., et al. (2019). "Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor". Nature, 574(7779), 505-510. URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1666-5

- ↑ James Temperton (Jan 26, 2017). "Got a spare $15 million? Why not buy your very own D-Wave quantum computer". Wired. URL: https://www.wired.com/story/d-wave-2000q-quantum-computer/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Google Quantum AI (December 9, 2024). "Willow: Exponentially reducing errors in quantum computing". URL: https://blog.google/technology/quantum-computing/willow-quantum-computing-chip/

- ↑ IBM Research (2024). "IBM Quantum Development Roadmap". URL: https://www.ibm.com/quantum/roadmap

- ↑ Boger, Yuval (March 8, 2024). "Why the QPU Is the Next GPU". Built In. URL: https://builtin.com/articles/qpu-quantum-processing-unit

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2000). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 978-0-521-63503-5.

- ↑ National Academies of Sciences (2019). "Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects". The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/25196

- ↑ Benioff, P. (1980). "The computer as a physical system: A microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers as represented by Turing machines". Journal of Statistical Physics. 22(5): 563-591.

- ↑ Feynman, R. P. (1982). "Simulating physics with computers". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 21(6): 467-488.

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (1985). "Quantum theory, the Church-Turing principle and the universal quantum computer". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 400(1818): 97-117.

- ↑ Shor, P. W. (1994). "Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring". Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 124-134.

- ↑ Monroe, C., et al. (1995). "Demonstration of a fundamental quantum logic gate". Physical Review Letters. 75(25): 4714-4717.

- ↑ Grover, L. K. (1996). "A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search". Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. pp. 212-219.

- ↑ The Quantum Insider (May 26, 2020). "The History of Quantum Computing You Need to Know". URL: https://thequantuminsider.com/2020/05/26/history-of-quantum-computing/

- ↑ Nakamura, Y., et al. (1999). "Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box". Nature. 398(6730): 786-788.

- ↑ Lisa Zyga (2011-06-01). "D-Wave sells first commercial quantum computer". Phys.org. URL: https://phys.org/news/2011-06-d-wave-commercial-quantum.html

- ↑ IBM News Room (November 16, 2021). "IBM Unveils Breakthrough 127-Qubit Quantum Processor". URL: https://newsroom.ibm.com/2021-11-16-IBM-Unveils-127-Qubit-Eagle-Processor

- ↑ Lee, Jane Lanhee (November 9, 2022). "IBM launches its most powerful quantum computer with 433 qubits". Reuters. URL: https://www.reuters.com/technology/ibm-launches-433-qubit-osprey-processor-2022-11-09/

- ↑ IBM Research (December 4, 2023). "IBM Quantum Condor: Breaking the 1000-qubit barrier". URL: https://research.ibm.com/blog/quantum-condor

- ↑ Atom Computing (October 24, 2023). "Atom Computing First to Exceed 1,000 Qubits". PR Newswire. URL: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/quantum-startup-atom-computing-first-to-exceed-1-000-qubits-301964712.html

- ↑ Quantinuum (March 2024). "Quantinuum achieves 'three 9s' fidelity in quantum operations". URL: https://www.quantinuum.com/news/three-nines-fidelity

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Nayak, Chetan (February 19, 2025). "Microsoft unveils Majorana 1, the world's first quantum processor powered by topological qubits". Microsoft Azure Quantum Blog. URL: https://azure.microsoft.com/blog/quantum/majorana-1-topological-qubits/

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Reuters (October 22, 2025). "Google says it has developed landmark quantum computing algorithm". URL: https://www.reuters.com/technology/google-quantum-echoes-algorithm-2025-10-22/

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Di Giovanni, Filippo (January 5, 2024). "Physical Principles Underpinning Quantum Computing". EE Times Europe. URL: https://www.eetimes.eu/physical-principles-quantum-computing/

- ↑ Clarke, J., & Wilhelm, F. K. (2008). "Superconducting quantum bits". Nature. 453(7198): 1031-1042.

- ↑ Rigetti Computing (December 23, 2024). "Rigetti Computing Reports 84-Qubit Ankaa-3 System Achieves 99.5% Median Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity". URL: https://investors.rigetti.com/news-releases/

- ↑ Monroe, C., & Kim, J. (2022). "Trapped-ion quantum computing". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 13: 237-261.

- ↑ IonQ (2024). "How We Achieved Our 2024 Performance Target of #AQ 35". URL: https://ionq.com/blog/aq-35-achievement

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Quantinuum (July 2023). "Quantinuum H2 Achieves Record Quantum Volume of 8,388,608". URL: https://www.quantinuum.com/blog/quantum-volume-milestone

- ↑ Bartlett, S. D. (2020). "Photonic quantum information processing: A concise review". APL Photonics. 6(4): 041303.

- ↑ Henriet, L., et al. (2020). "Quantum computing with neutral atoms". Quantum. 4: 327.

- ↑ Evered, S. J., et al. (2023). "High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer". Nature. 622: 268-272.

- ↑ Krantz, P., et al. (2019). "A quantum engineer's guide to superconducting qubits". Applied Physics Reviews. 6(2): 021318.

- ↑ Cross, A. W., et al. (2019). "Validating quantum computers using randomized model circuits". Physical Review A. 100(3): 032328.

- ↑ "How quantum computing is changing molecular drug discovery". World Economic Forum. January 2025. URL: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2025/01/quantum-computing-drug-discovery/

- ↑ JPMorgan Chase & Quantinuum (March 2025). "Certified quantum randomness for financial modeling". URL: https://www.jpmorgan.com/technology/news/certified-randomness

- ↑ Gidney, C., & Ekerå, M. (2021). "How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits". Quantum. 5: 433. URL: https://quantum-journal.org/papers/q-2021-04-15-433/

- ↑ Biamonte, J., et al. (2017). "Quantum machine learning". Nature. 549(7671): 195-202.

- ↑ Preskill, J. (2018). "Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond". Quantum. 2: 79.

- ↑ "The year of quantum: From concept to reality in 2025". McKinsey & Company. Retrieved November 3, 2025. URL: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/quantum-2025